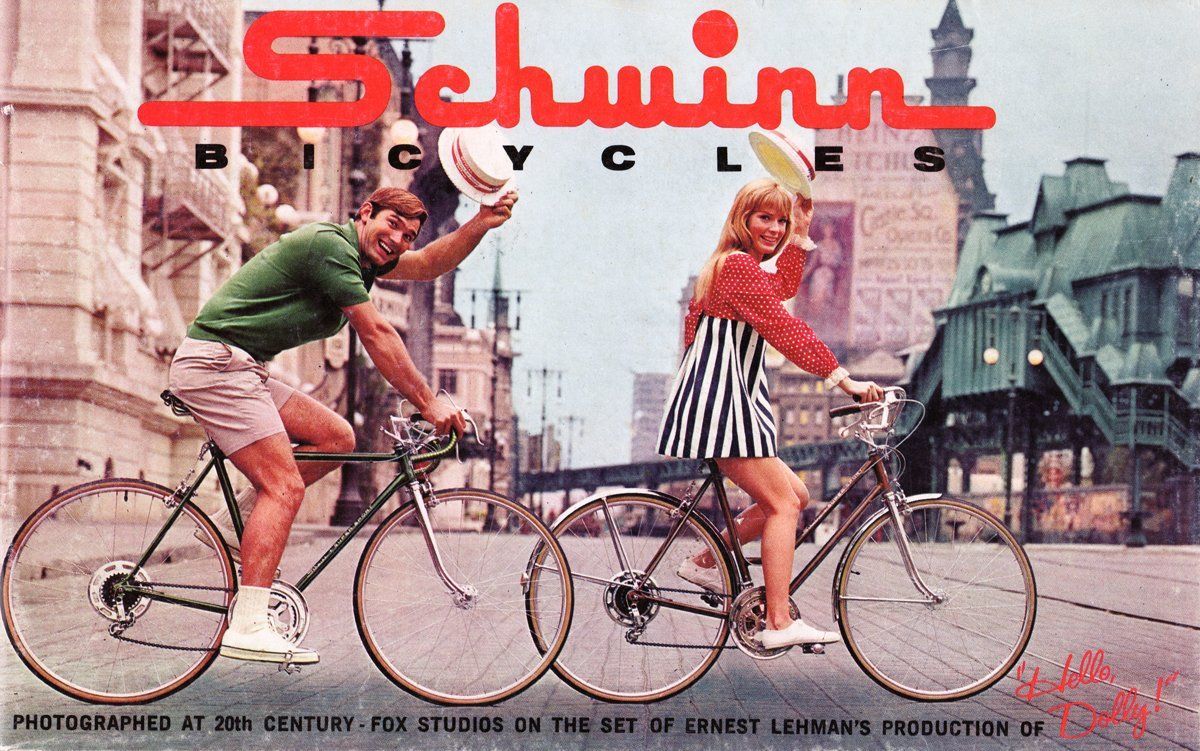

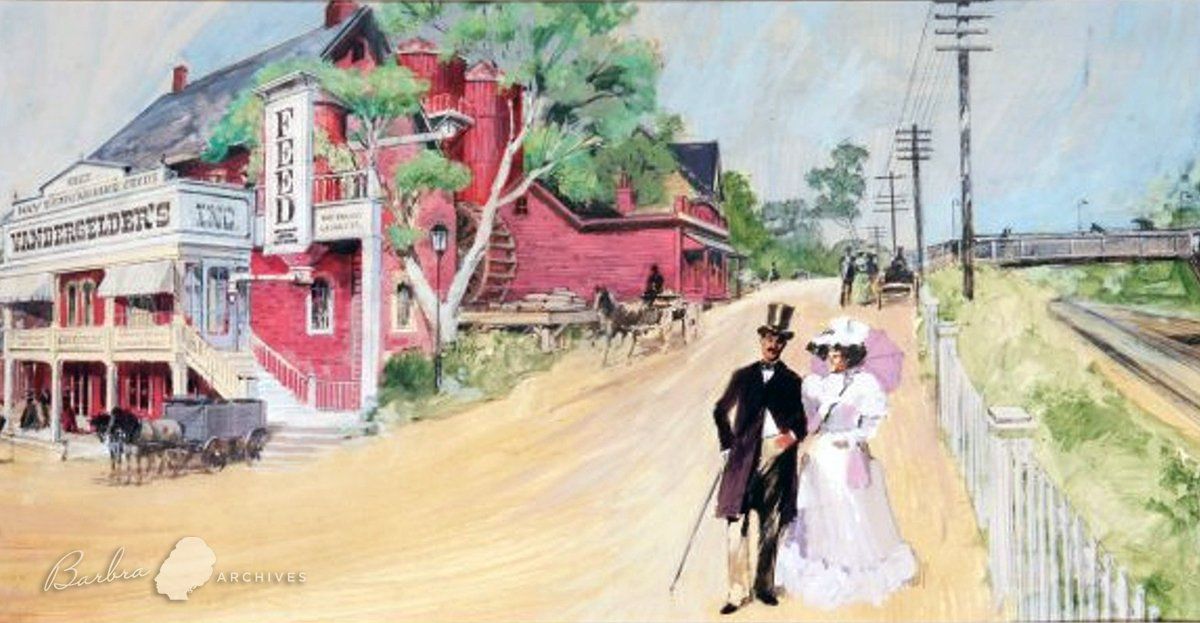

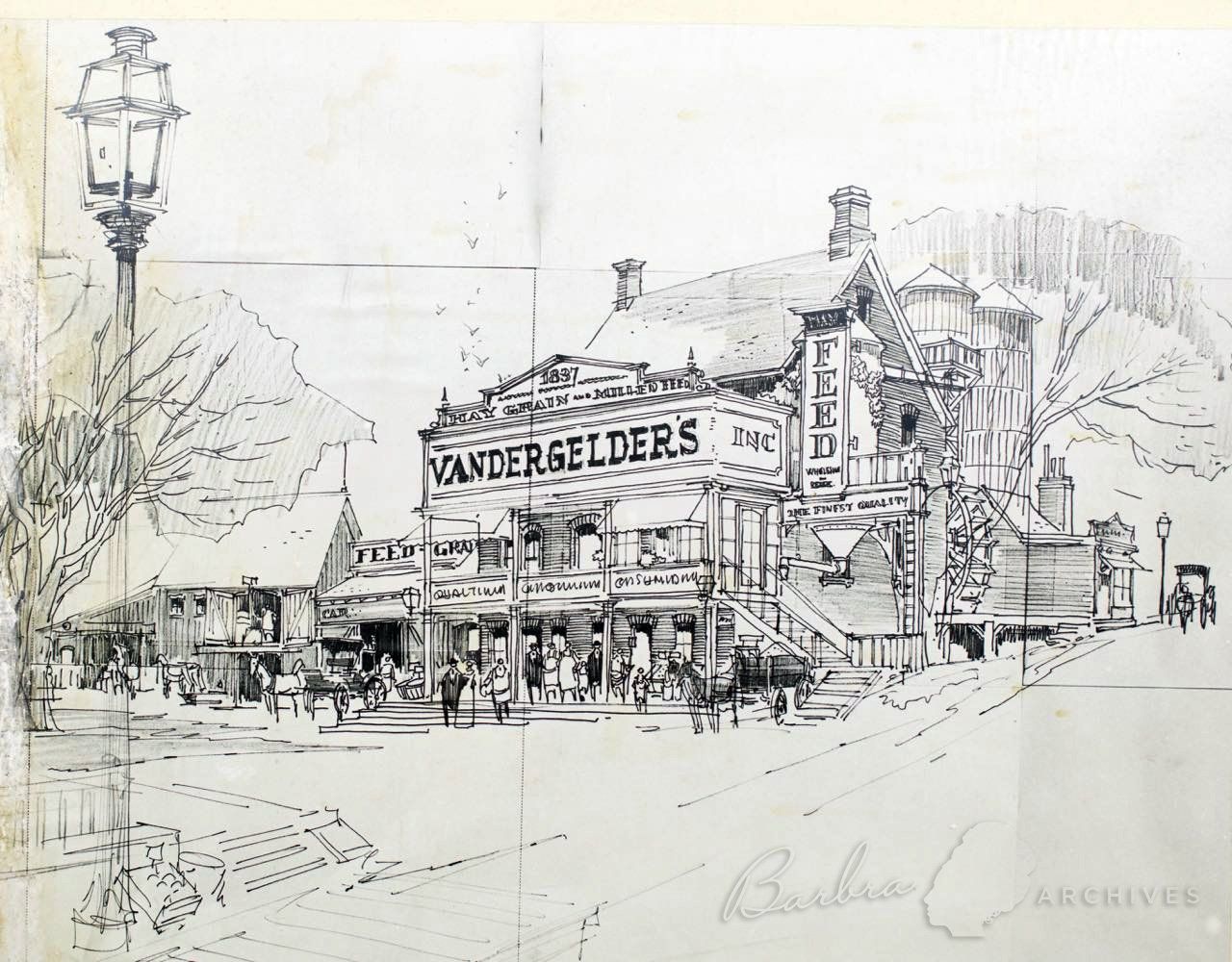

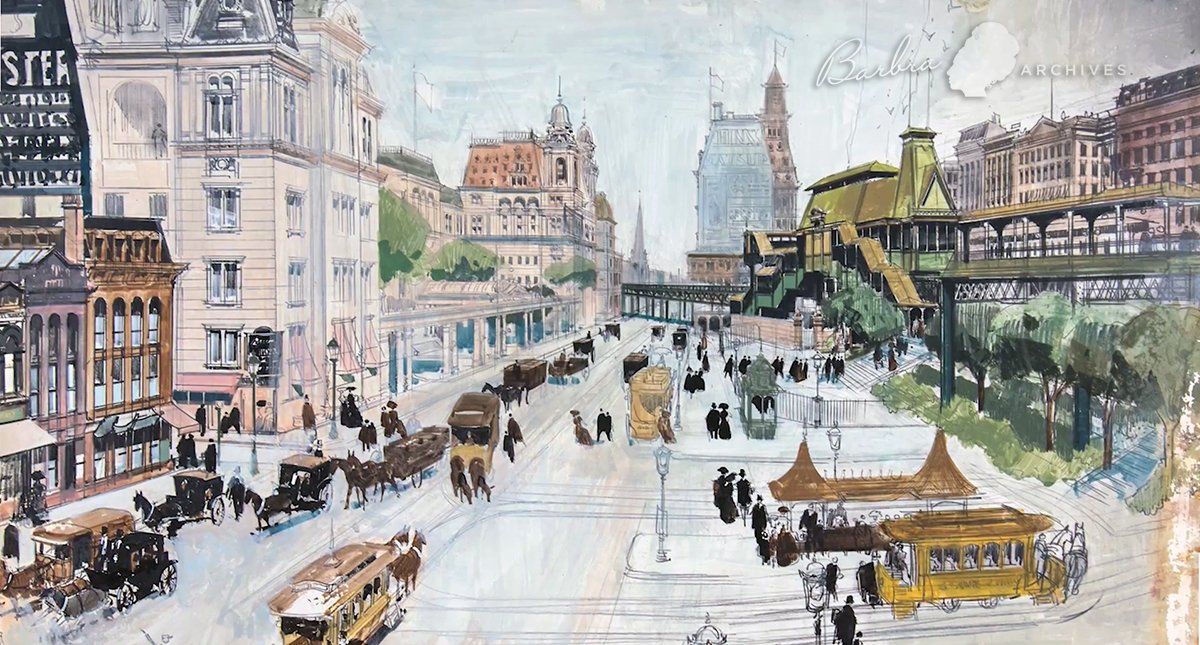

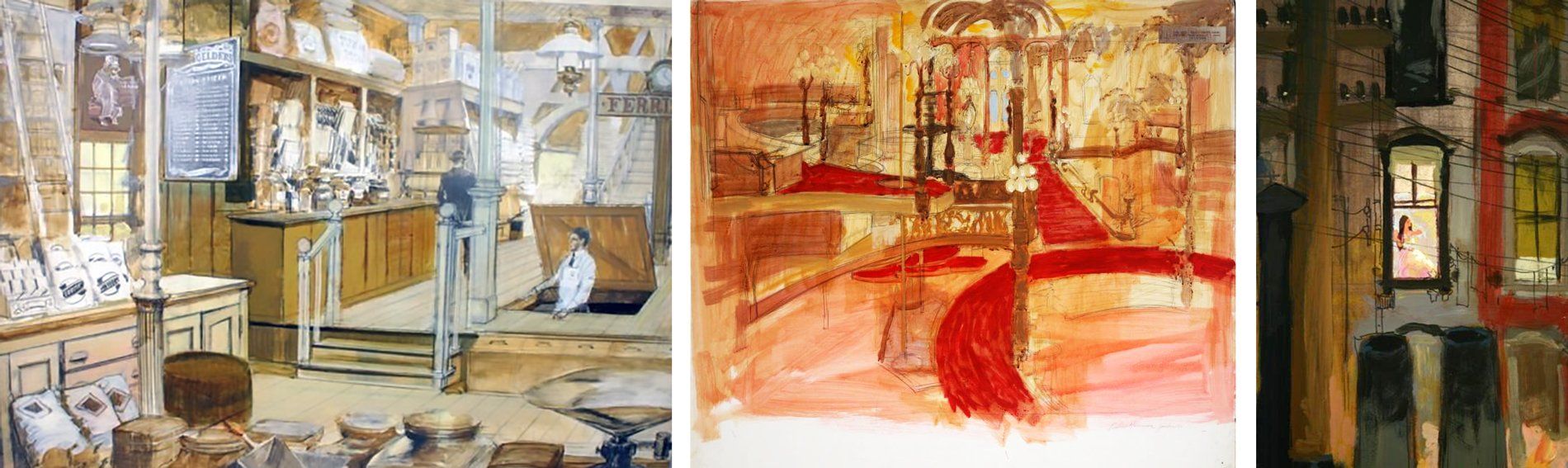

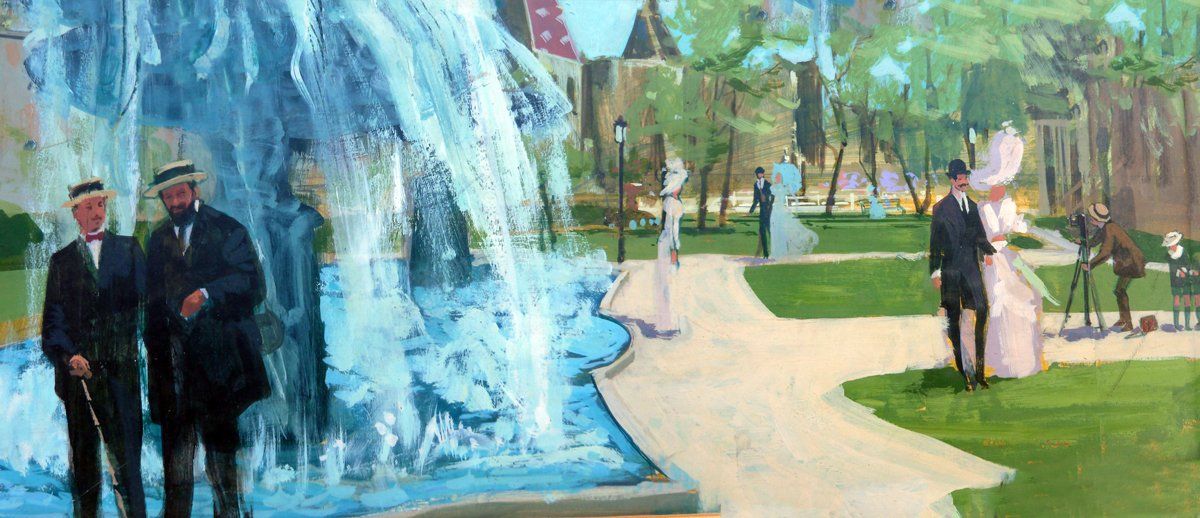

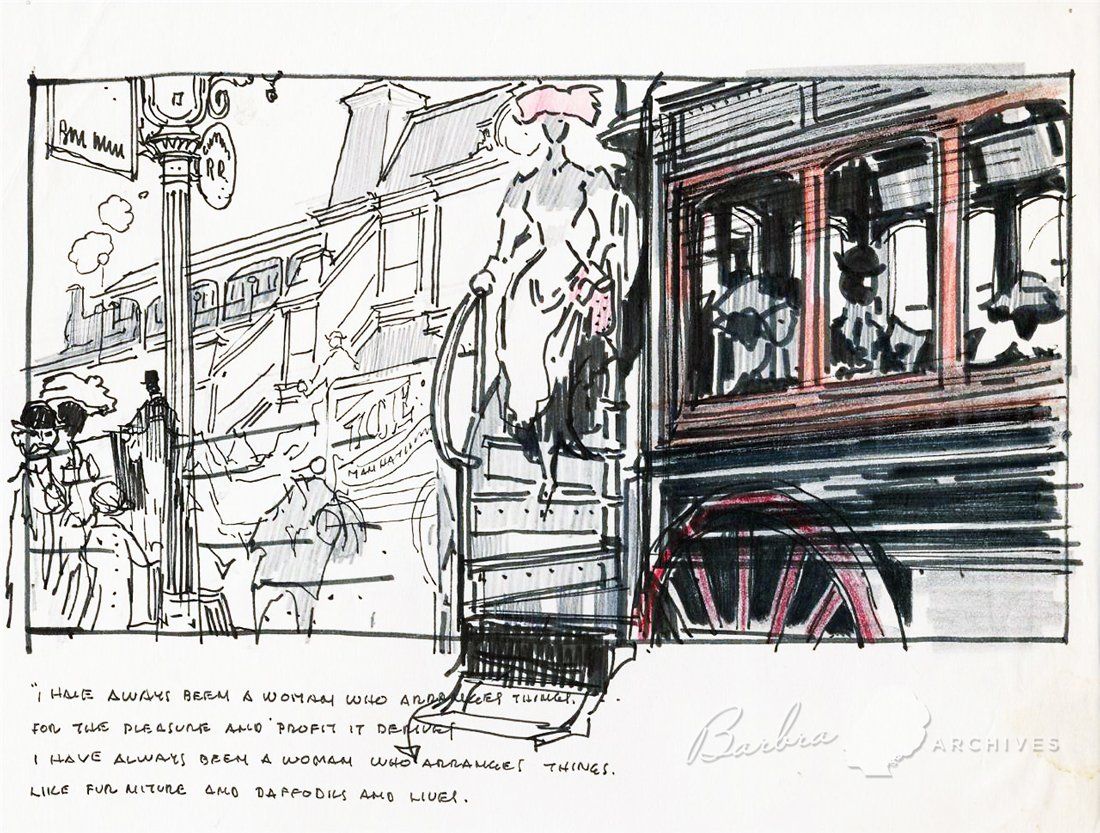

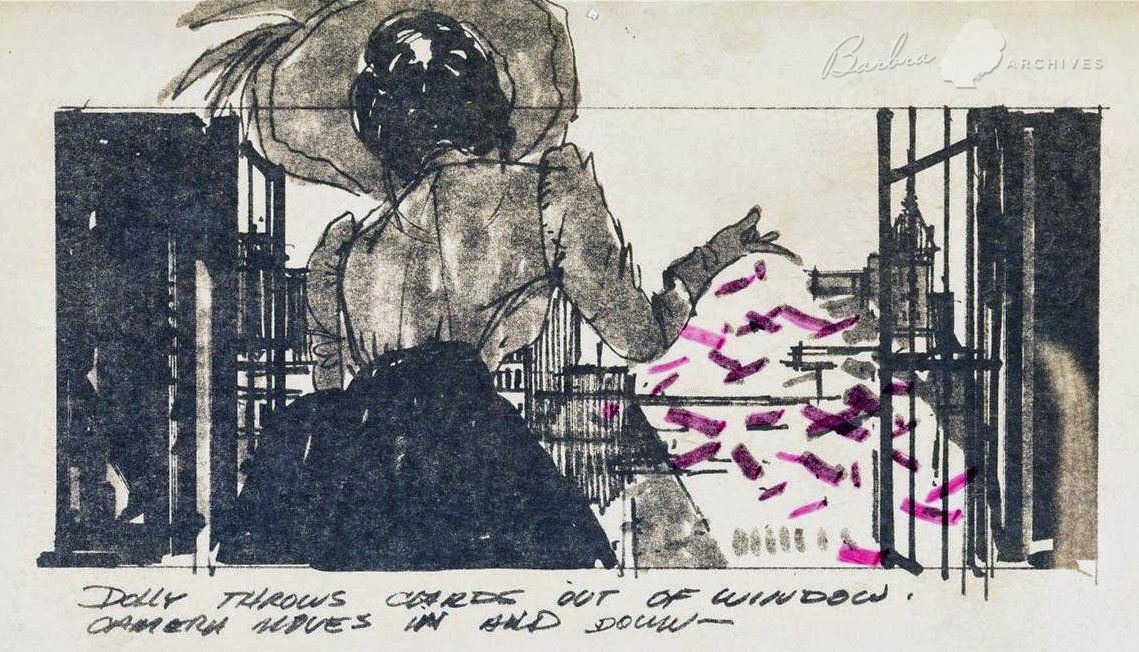

One of the main reasons for Dolly’s high cost was the problem of depicting New York City in the 1890s. It would not have been possible to film on location in New York in 1968, nor would it have been historically accurate.

Therefore, Twentieth Century Fox developed a budget for filming Dolly in Rome, Italy. Richard Zanuck balked. “Jesus, you can get away with shooting Cleopatra in Rome,” he told John Gregory Dunne, “but Hello, Dolly! is a piece of hard-core Americana. You shoot that in Rome and the unions back here will raise such a stink you’ll have a hard time getting over it. It would have tarnished the image of the whole picture.”

It was also discovered that shooting in Rome would save them only a few million dollars – hardly worth the trouble.

Lehman considered rehabilitating the old Atlanta set from Gone with the Wind, which was still standing at Desilu Studios. That idea was vetoed because Fox didn’t want to leave an expensive set standing at another studio.

For a brief while, the production entertained the idea of building 1890’s New York as a miniature (at a cost of around $345,325 dollars).

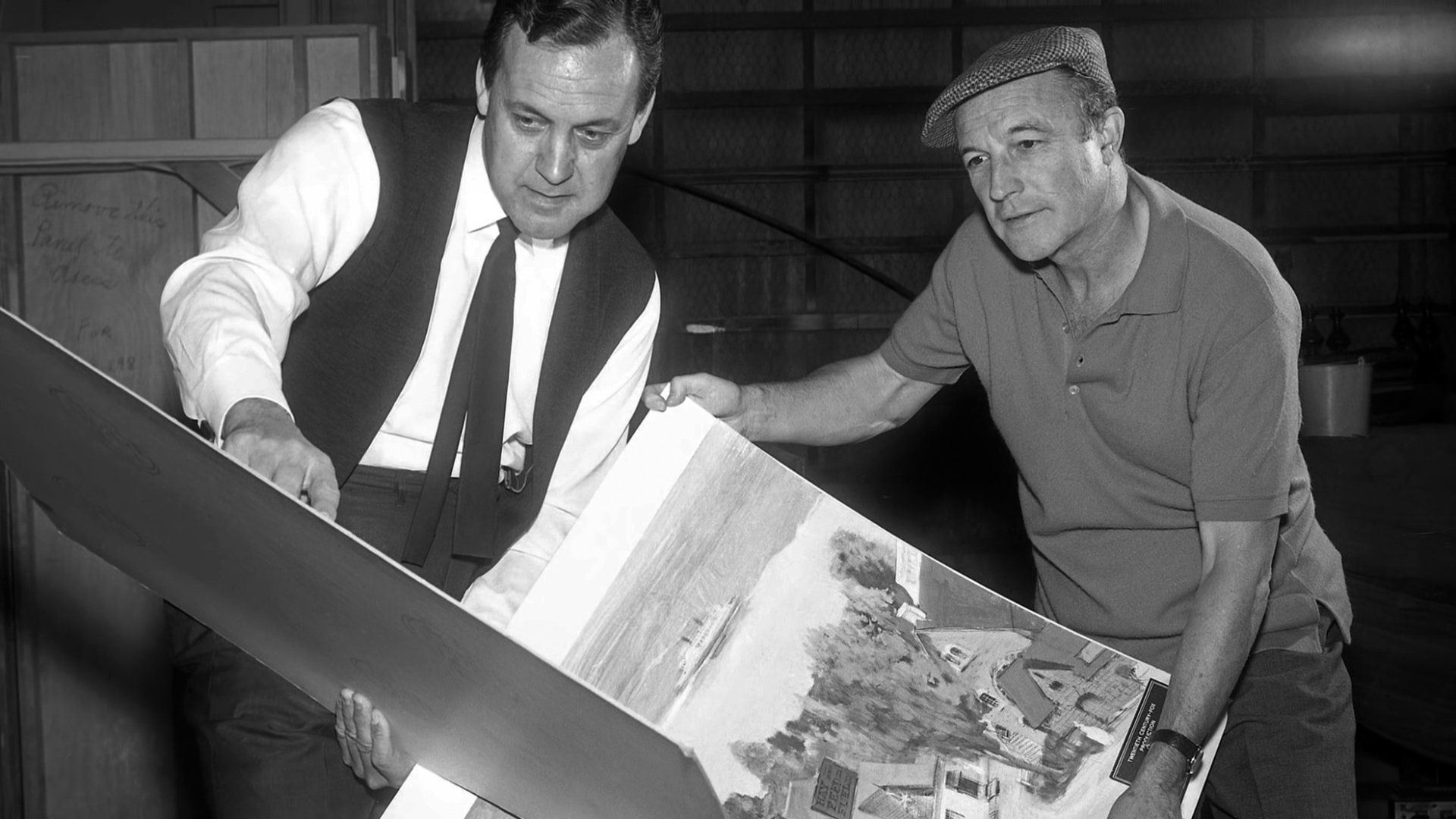

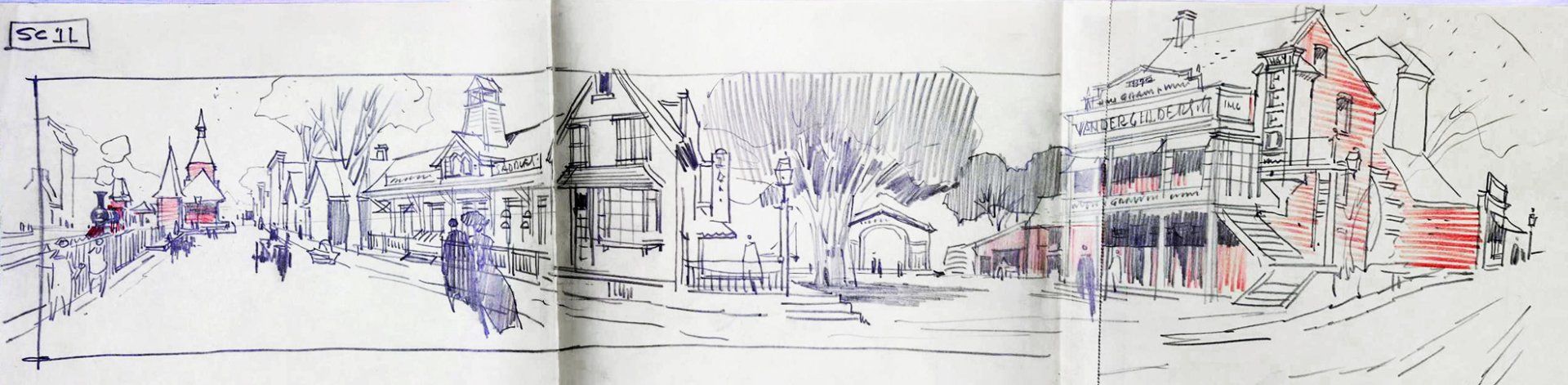

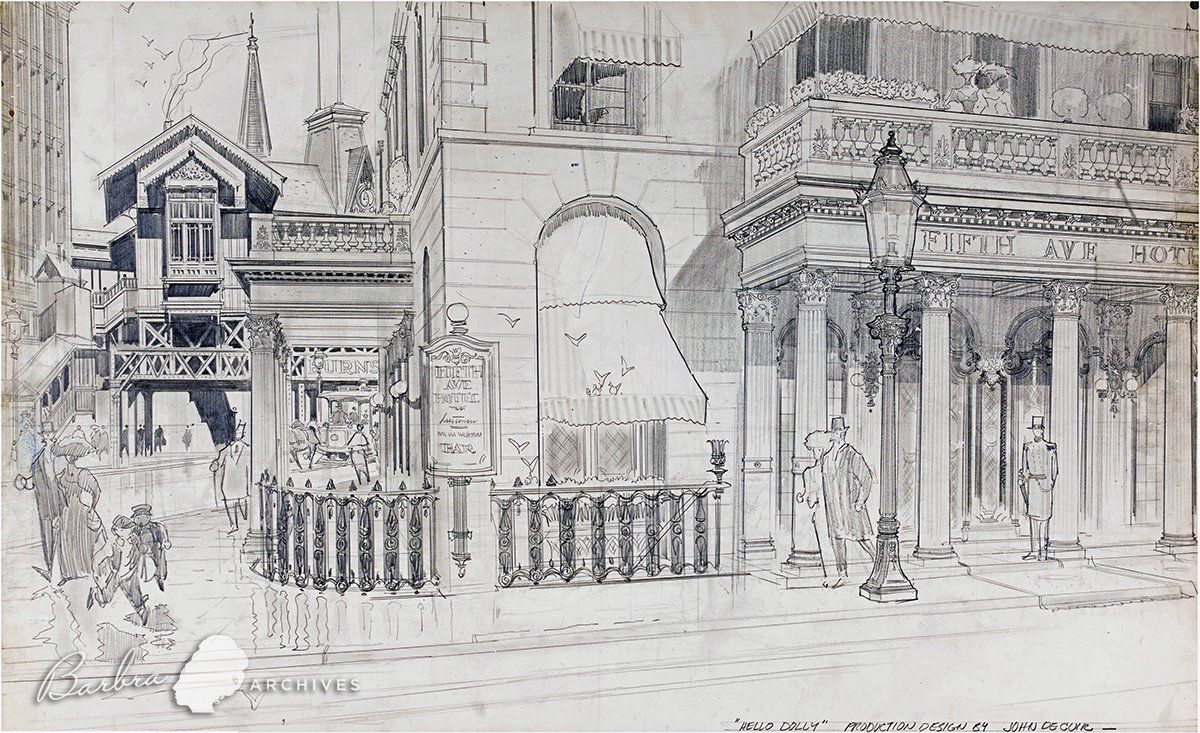

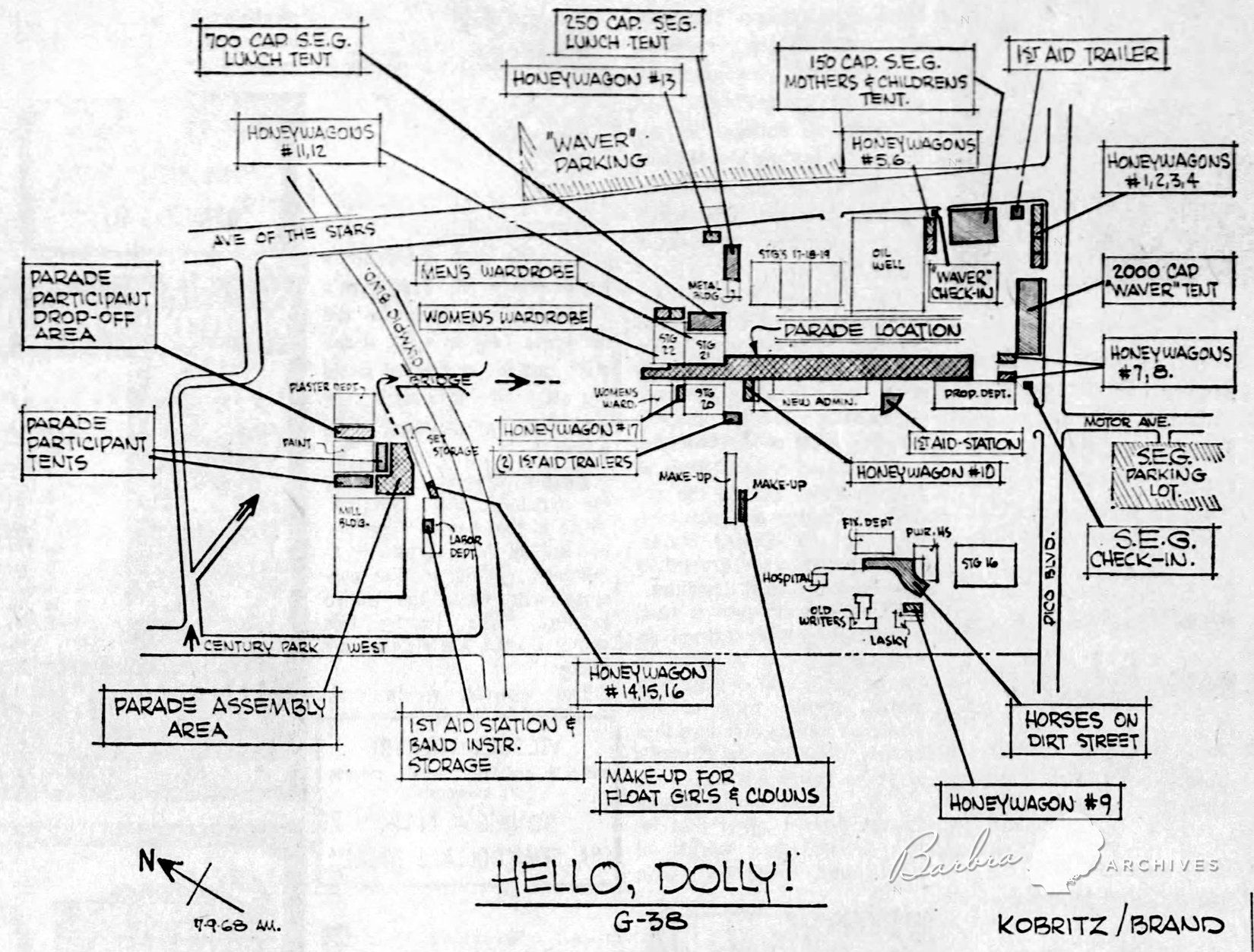

Fox next considered building the New York set at their ranch (which was sold in the 1970s and is known today as Malibu Creek State Park). John DeCuir told the New York Times the set at the Fox ranch would have cost $7 million dollars. “We actually leveled 40 acres including the old How Green Was My Valley set,” he said. “We spent $120,000 leveling the land before we discovered the unions wouldn't let us have workmen report directly to the ranch. After we estimated the cost of transporting everybody from the studio and transporting all the materials, including all the ornate architecture which had to be built in the studio mill and all the time lost in traveling, Dick Zanuck said ‘You're going to do it for a million and a half and you're going to do it in the vicinity of the studio.’”

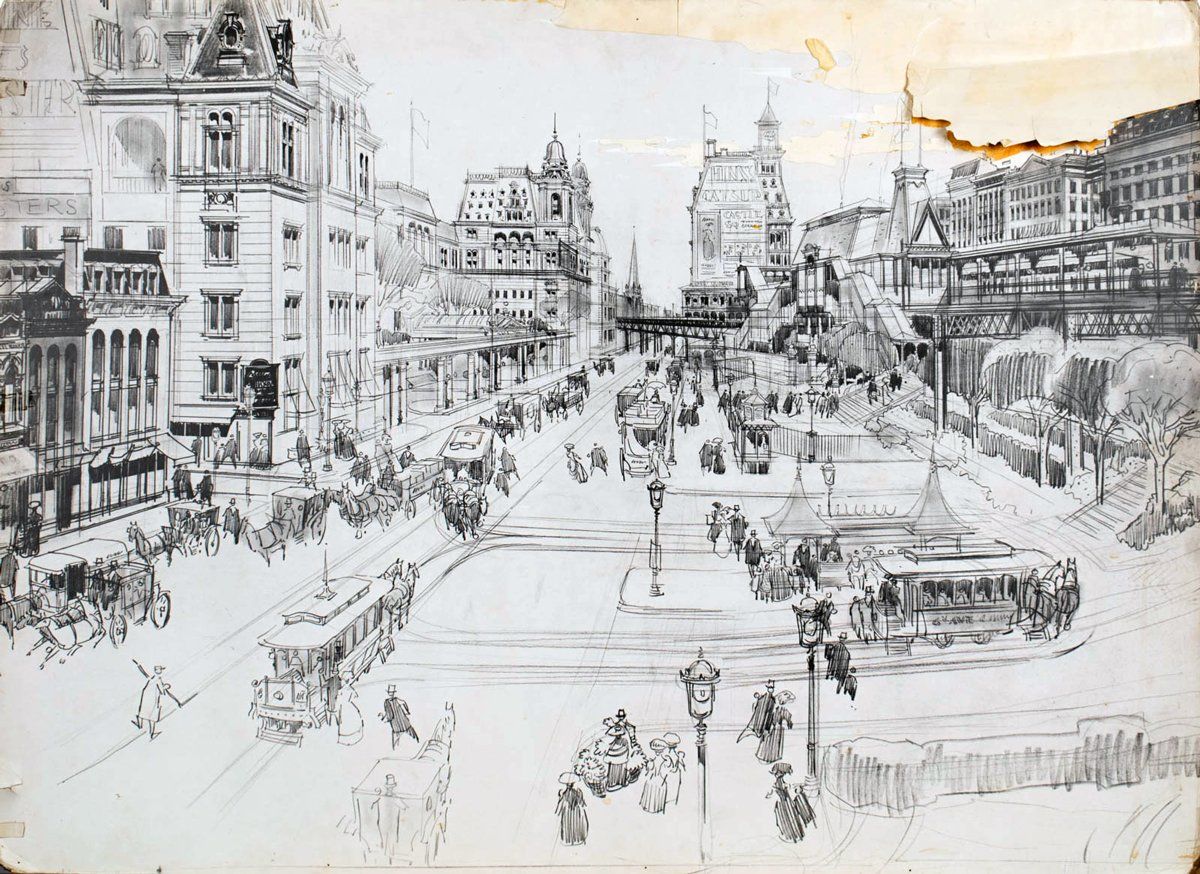

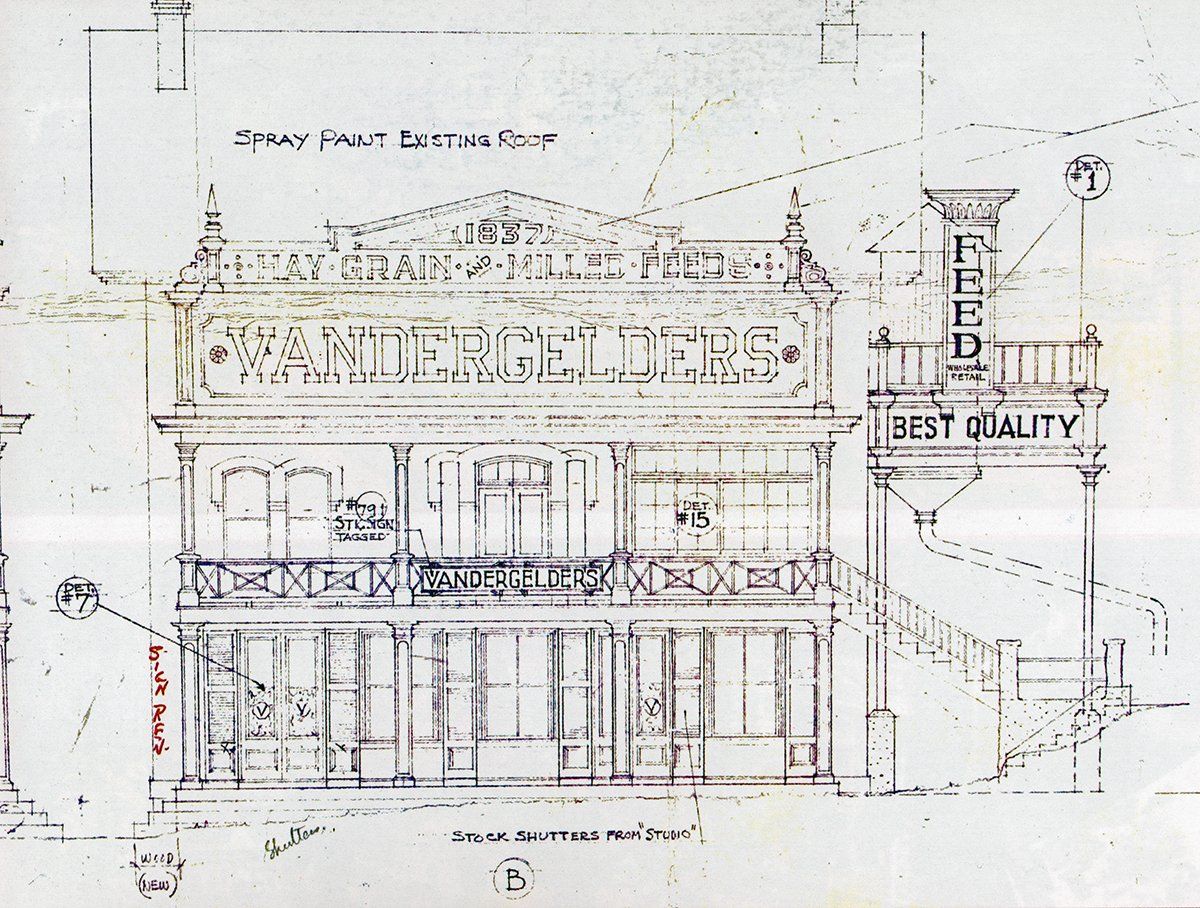

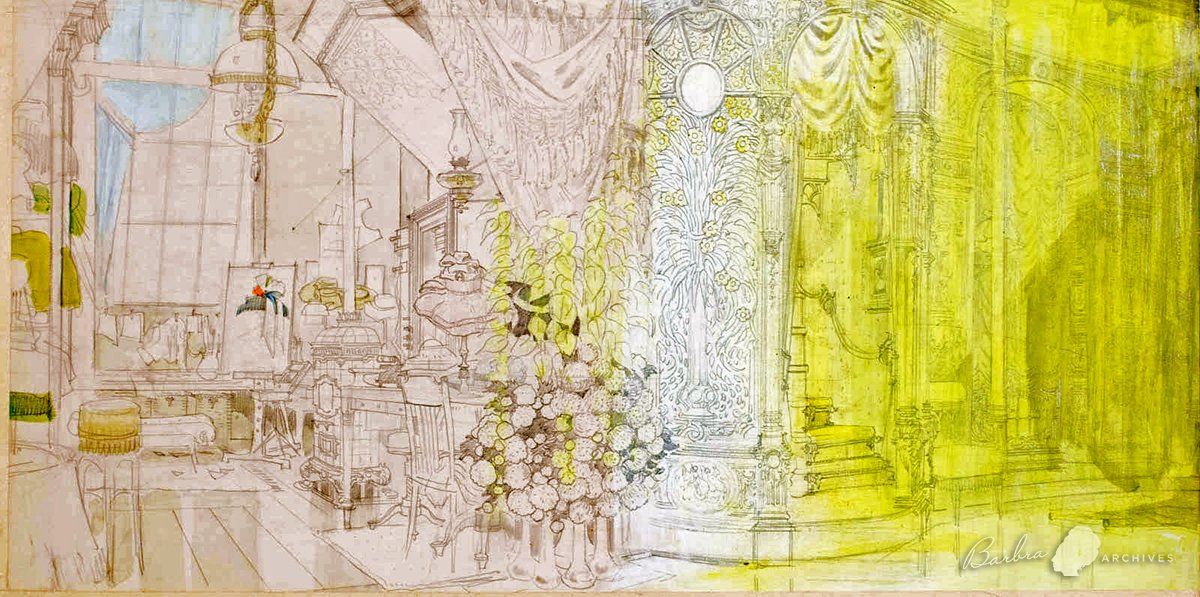

This was 1967 – years before CGI (Computer-Generated Imagery) effects were possible, which is how the mammoth task of recreating New York City would probably be handled today. So DeCuir drew up plans for a New York set that would be built on Fox’s main lot in Westwood, between Pico and Olympic boulevards.

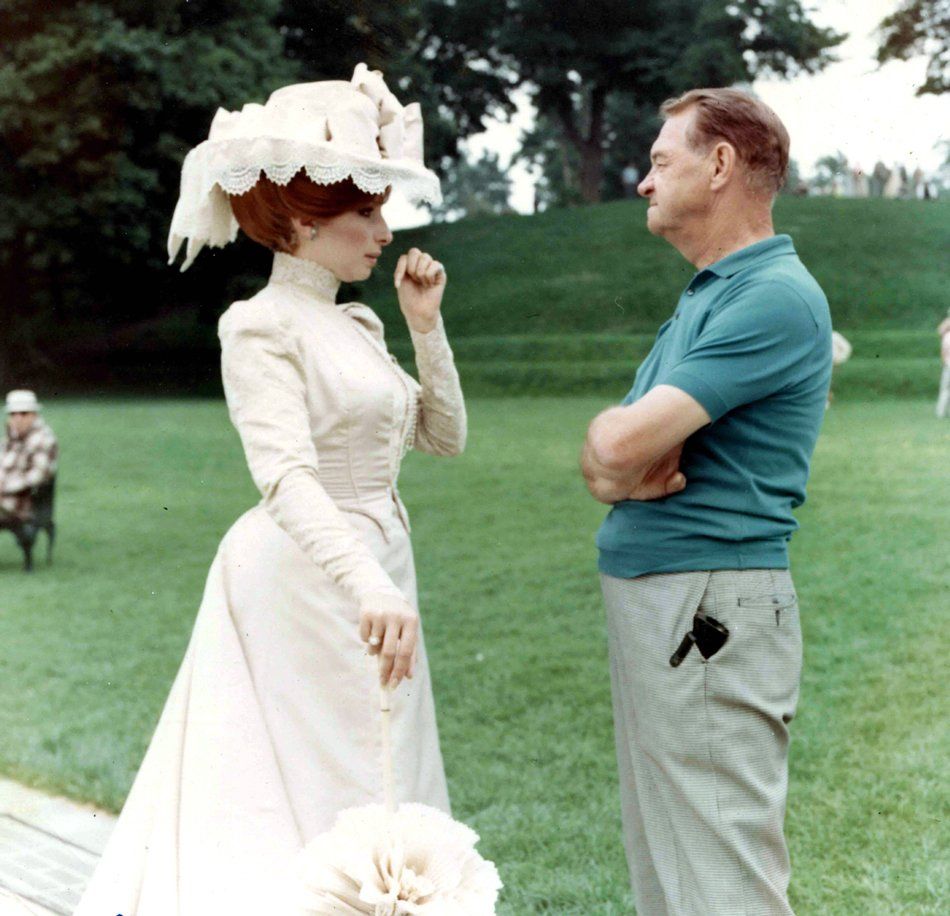

“There was no other way,” Gene Kelly declared. “I looked high and low everywhere and could find no place that so much as slightly resembled the Manhattan of 80 years ago.”