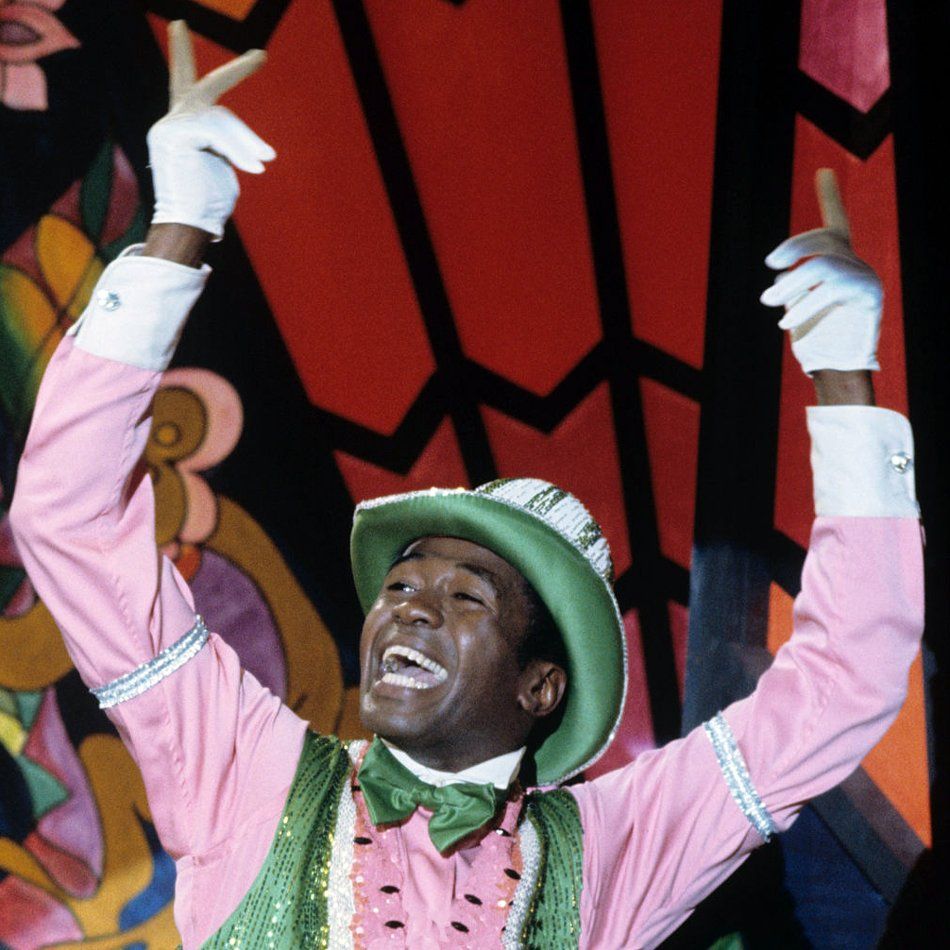

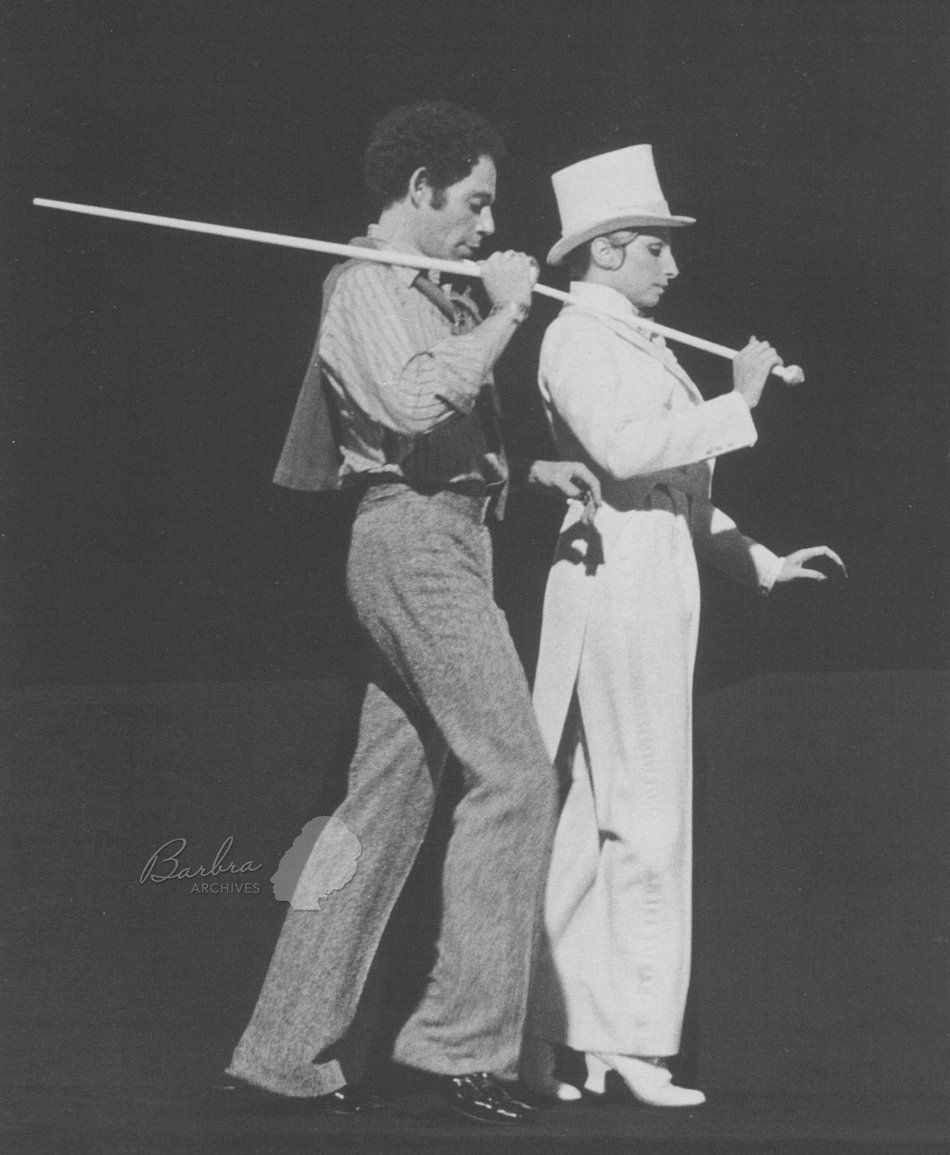

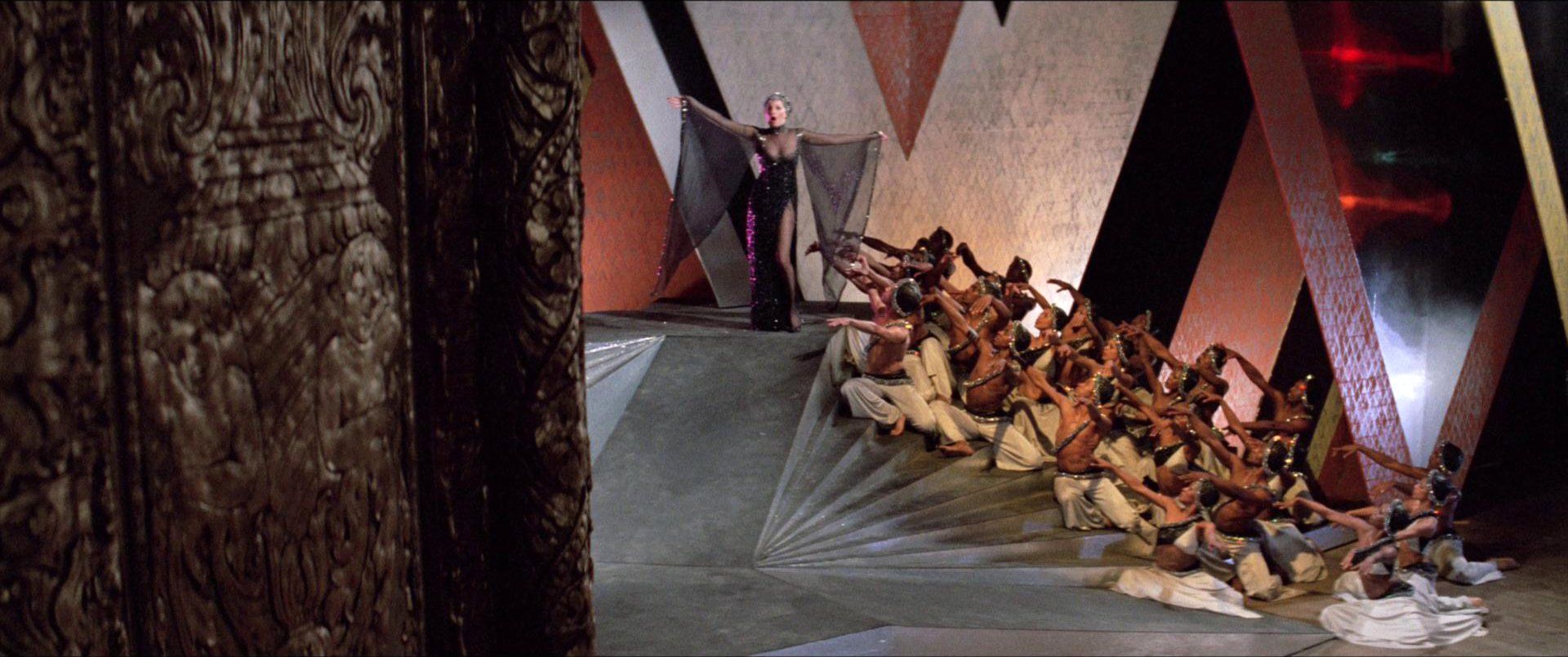

The big musical number “Great Day” was composed by Vincent Youmans, with lyrics by Edward Eliscu and Billy Rose. In Funny Lady, it’s staged as a big production number, gospel-style, with Barbra Streisand surrounded by African American dancers. She sings the song in an ensemble that costume designer Bob Mackie described as a “gun metal chiffon bugle beaded gown.”

“Great Day” has been criticized for being anachronistic – Fanny Brice certainly never sang or performed the song in such a manner. But it’s entertaining, nonetheless.

Most of the dancers in the number were part of Lester Wilson’s dance troupe. Wilson, a black choreographer, was a featured dancer in Sammy Davis Jr.’s musical Golden Boy, and just a few years later was choreographer on the disco dancing John Travolta film Saturday Night Fever.

Dancer Larry Vickers was not part of the troupe but was recruited to work on the movie. “I couldn't get over the fact that she needed 35 black dancers,” he said. “How was she going to get that many black dancers in California?” Once he arrived at rehearsals, Vickers was impressed. “I learned who all these people were, from Lorraine [Fields] to Michelle Simmons, and of course Lester, and all these amazing, amazing dancers,” he said. “I'm talking about Mabel Robinson and Jerry Grimes and Gary Chapman and Bruce Heath. These were talented, talented, super talented people.”

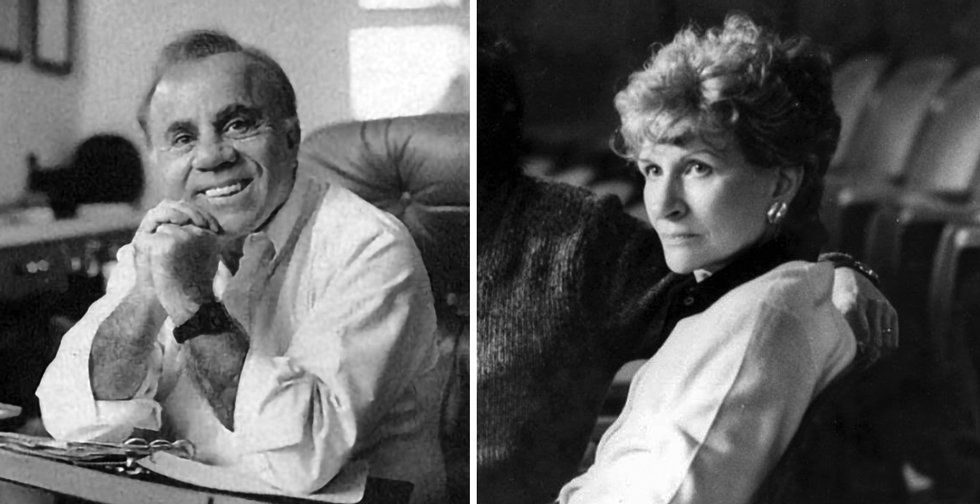

In rehearsal, Nora Kaye (Herb Ross’s wife) was choreographing the number, “but they weren't having any luck at all,” Larry Vickers said. “She was trying to do something that she thought could be black, with all this jungle-bunny stuff and knee slides. But it wasn't working.”

Instead, Lester Wilson choreographed the number in a day and a half.

The stage set – a beautiful construction of Art Deco ramps with Streisand perched at the top — was problematic. “There was not one solid square foot of anything,” Vickers shared. “It was all ramps and stairs and things of that nature. There was absolutely nothing flat to it. To think that we were supposed to dance on this was simply amazing.”

“So we were there a couple of months. And we only had that one number. And we'd worked it out a day and a half in … we still only had an hour or two of work to do every day,” said Vickers.

“We'd go through our number once or twice, and then we'd play ‘bid whist’ [a card game] the rest of the day.”

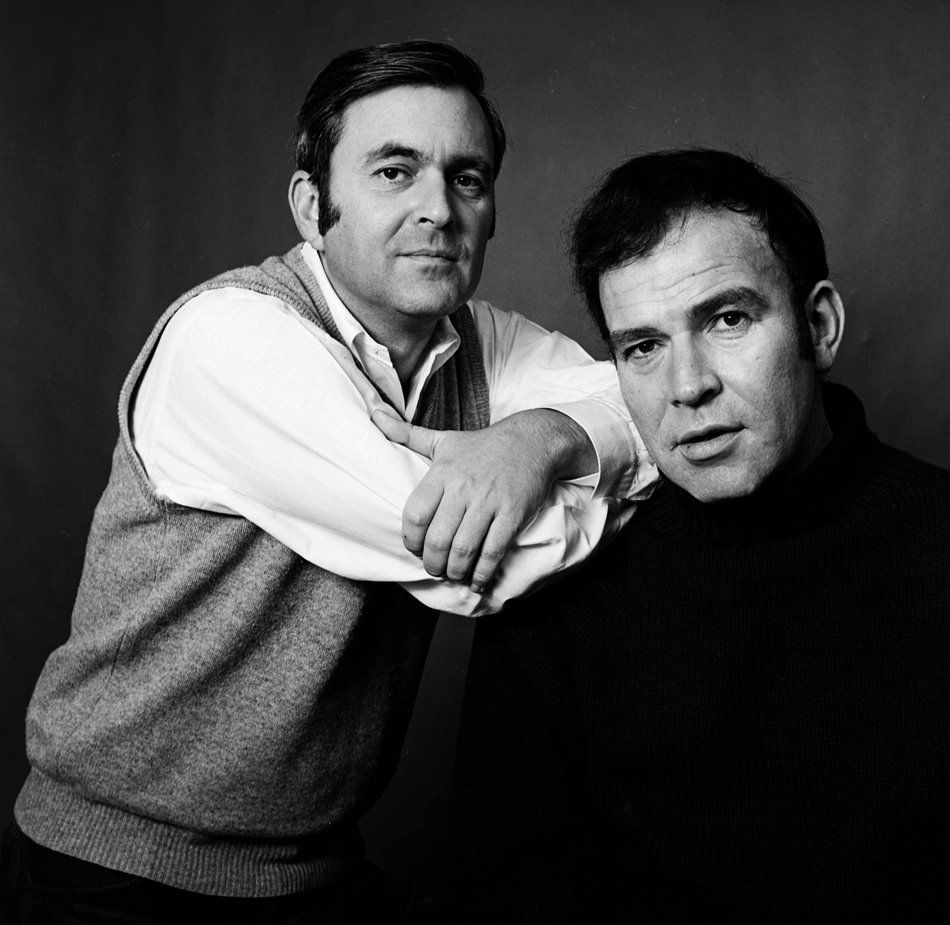

One day, the dancers ran the number for director Herb Ross, who proceeded to restage it. “Needless to say, everyone was disheartened. He was the director. So we did it. We weren't sure why we were being asked to redo everything, but we did it anyway,” Larry said.

The problems with “Great Day” did not end after it finished filming. In early January 1975, Herb Ross, Nora Kaye and Marvin Hamlisch assembled an orchestra at the Goldwyn Studios scoring stage and spent a considerable amount of time redoing Peter Matz’s original orchestration for “Great Day.” Reportedly, Streisand liked her vocal track, but not Peter Matz’s arrangement. Marvin Hamlisch was brought in to replace the orchestration.

The Matz and Hamlisch arrangements of “Great Day” can be heard on the two different Funny Lady

soundtrack albums released over the years. The original album, released in 1975 on vinyl, contains Hamlisch’s arrangement, which is the one we hear in the film. The 1998 Funny Lady

soundtrack CD is the Matz version of “Great Day.” From the minor chords that Streisand sings slowly at the beginning, to the complex middle-section (clapping hands, gospel piano, call-and-response with Barbra and the chorus), the difference between the two are obvious, and perhaps Matz’s version was considered to be too “Vegas Gospel.”